Typography - Task 1: Exercises

29.03.2022 - 26.04.2022 / Week 1 - Week 5

Tow Wan Tian / 0343765

Typography

/ Bachelor of Education / School of Education

Task 1 / Exercises

LECTURES

Week 1

The module coordinator, Mr Vinod, gave us an introduction to the Module. He explained the use of the Facebook group to access important information and announcement. He also briefed us about the Module Information Booklet.

1. Early letterform development: Phoenician to Roman

Direction of Writing

|

|

| Figure 1. The evolution of Phoenician letters. |

|

| Figure 1.1 Boustrophedon, a writing style developed by the Greeks. |

|

| Figure 1.2 Boustrophedon inscription on a wall in the Agora at Gortyn, Crete, Greece. |

|

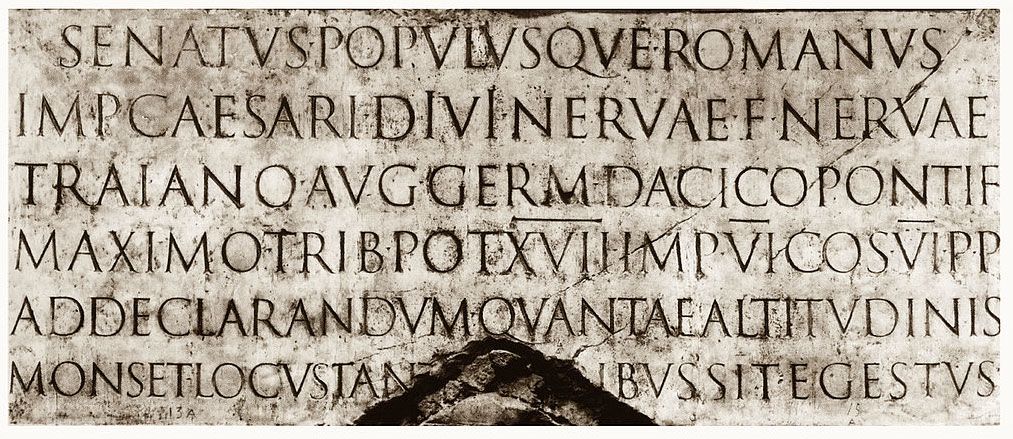

| Figure 1.3 An inscription incised at the base of Trajan’s Column in Rome occurred in 113 CE. |

|

| Figure 1.4 Rustic capitals from a manuscript of Virgil's Aeneid (the “Vatican Virgil”), 4th century AD. |

|

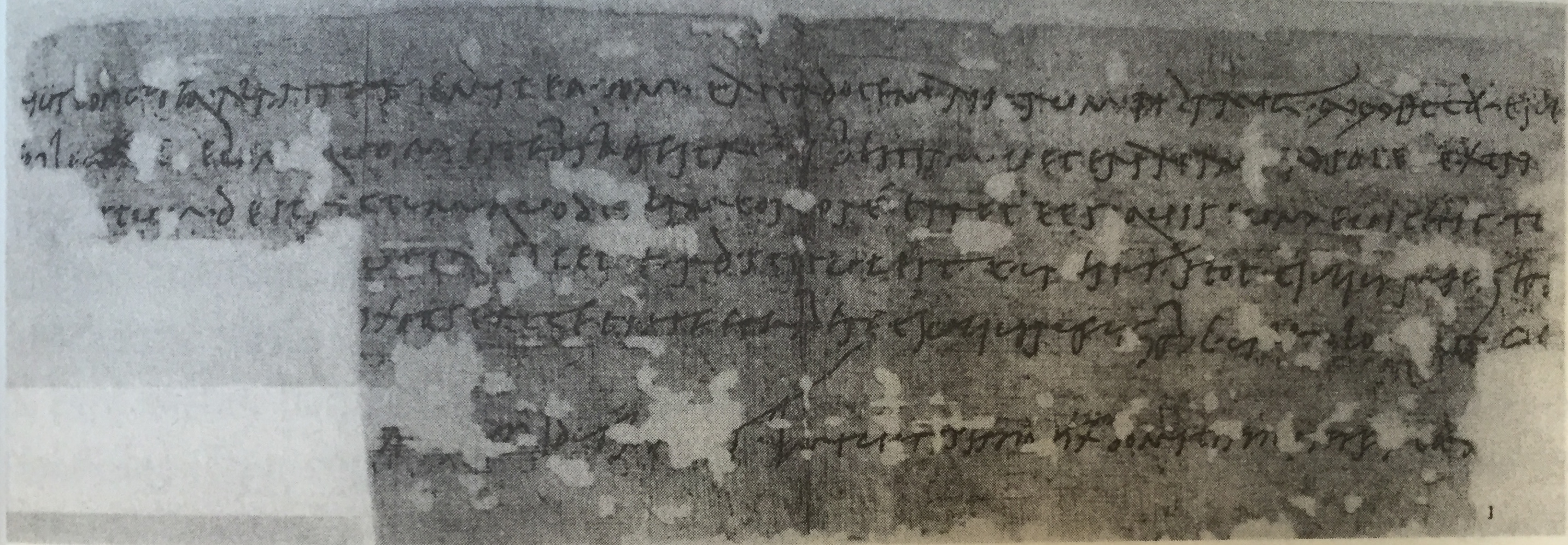

| Figure 1.5 Old Roman cursive hand wrote on a horse sales contract of the era 77 CE. |

|

| Figure 1.6 Uncial book hand. |

|

| Figure 1.7 Half-Uncials. |

|

| Figure 1.8 Blackletter. |

- 1450 Blackletter - Earliest printing type. Based on hand-copying styles used in books from Northern Europe

- 1475 Oldstyle

- 1500 Italics (with serifs - italics, without serifs - oblique)

- 1550 Script

- 1750 Transitional - refinement of Oldstyle

- 1775 Modern - unbracketed with the contrast of thick and think strokes

- 1825 Square Serif/Slab Serif

- 1900 Sans Serif (Sans means without)

- 1990 Serif/Sans Serif

|

| Figure 1.9 Text typeface classification based on Alexander Lawson. |

Week 2

1. Describing Letterform

|

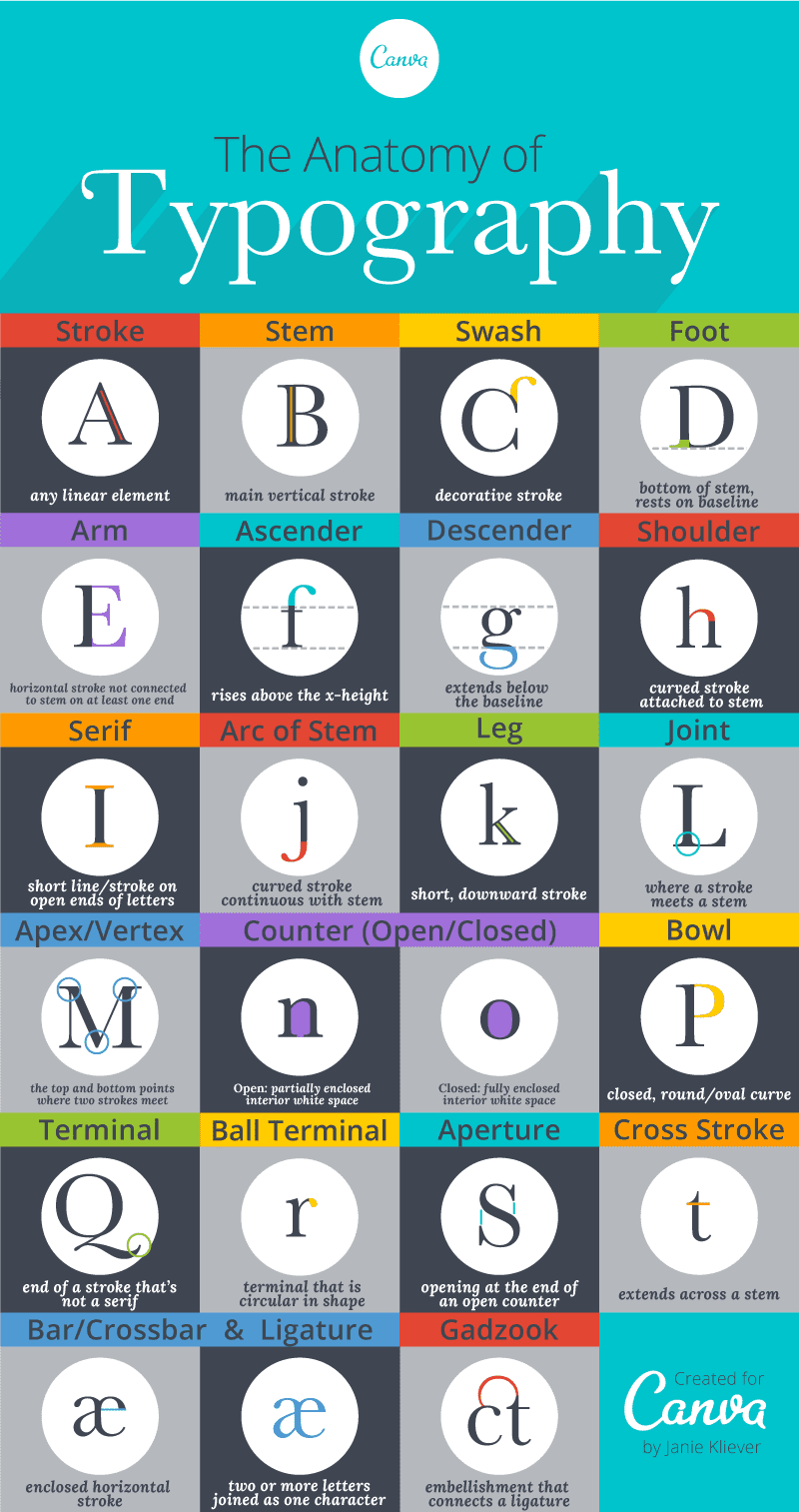

| Figure 2. An infographic of the terminologies used to describe a letterform by Canva.com. |

Baseline - The imaginary line of the visual base of the letterform.

Median - The imaginary line that forms the x-height of the letterform.

X-height - The height in any typeface of the short form.

Stroke - Any line that defines the basic letterform.

Apex/Vertex - The point created by joining two diagonal stems (Apex = a point above, Vertex = a point below).

Arm - Horizontal and/or inclined upward short strokes of the stem of the letterform (e.g E, T, K).

Ascender - The portion of the stem of a lowercase that goes above the median. (e.g b, d).

Beak - The half-serif finish on horizontal arms.

Bowl - The rounded form that defines a counter, either open or closed.

Bracket - The transition between a serif and the stem.

Cross Bar - The horizontal stroke that connects two stem strokes.

Cross Stroke - The short horizontal stroke that goes across the stem of a letterform (e. f, t)

Crotch - The interior space where two strokes meet.

Ear - The stroke that extends out from the main stem.

Em/En - Em is the distance equal to the size of the letterform. En is half of an em.

Finial - The rounded non-serif terminal to a stroke.

Leg - The short stroke off the stem, either at the bottom or incline downward.

Ligature - The character formed by the combination of two or more letterforms (e.g fl).

|

| Figure 2.1 An example of ligature of the combination of 'fi' and 'fl'. |

2. The Font

The full font of a typeface includes all 26 letters, the numerals and a few punctuation marks.

Generally, the type families would have the following:

- Uppercase and Lowercase

-

Small capitals - Uppercase letterforms drawn to the x-height of

the typeface

- Uppercase numerals - aka lining figures which have the same height as the uppercase.

- Lowercase numerals - aka old style figures or text figures. Commonly seen in serif typeface letterforms.

-

Italics

- Punctuations and miscellaneous characters

- Ornaments

Roman - The term derived from inscriptions on Roman monuments. The slightly thinner stroke in roman is 'book'

Italics - Designed based on handwriting

Oblique - Design that is not based on handwriting

Boldface - Thicker stroke

Light - Thinner stroke

Condensed - Compressed

Extended - Widened

Week 3

1. Tracking: Kerning and Letterspacing

Kerning - Adjusting the space between letters.

Letterspacing - Adding space between letters

Tracking - Adding and/or removing space in a word and sentence.

So when do designers use add letter space to their design? A common practice is letterspacing uppercase letters. Generally, many typefaces are not designed to be used as uppercase. Using all uppercase for a word may cause it to appear condensed and crowded. Adding letters space allows a breather to the eye.

Designers always letter-space uppercase letters, though some may disagree with the practice. However, there has been greater resistance to letterspacing lowercase letters. DO NOT letter-space lowercase letters as it can break the counter form of letters (aka the negative parts inside and around letters) and affect the readability of the text.

|

| Figure 2.2 Side-by-side comparison of the outcome of normal tracking and loose tracking to a piece of text (screenshot of lecture slides). |

Flush Left (Ragged right) - Closely mirrors the asymmetrical experience of handwriting. Each line starts at the same point but ends wherever the last word of the line ends. Spaces between words are consistent, thus creating an even grey value. Using the Flush Left alignment creates ragging on the right of the text. It is advised to maintain smooth ragging.

Centred (Ragged right and left)- Symmetrical alignment of text. This format assigned equal value and weight to both ends of each line. It transforms a body of text into shape, adding pictorial quality to the material. It is important to amend line breaks so that the text does not appear too jagged. It is not advisable to use centred alignment for long pieces of text. Due to its nature of irregular starting point, it makes it hard to read, thus, it should be used sparingly.

Flush Right (Ragged left) - It is aligned at the end of a line. More useful in situations such as captions for images.

Justified - This format imposes a symmetrical shape on the text. It is

achieved by reducing and increasing the space between words. This format can

often result in producing 'rivers' (the unusual gap between words or letters)

of white space in the text. Avoid the 'rivers' as much as possible.

|

|

| Figure 2.3 An example of flush left, flush right, centred and justified text alignment. |

3. Texture

Different typefaces suit different messages. Typographers and designers should know which typeface best suits the message at hand. We should consider the texture of a typeface as well. To examine the texture of a typeface, we should look at the contrast between its thin and thick strokes, and the proportion of the x-height relative to its ascender and descender. A type with a larger x-height or heavier stroke may produce a darker grey value, whereas a type with a smaller x-height or lighter stroke may cause a lesser grey value.

How do the x-height, ascender and descender affect readability? If the x-height is relatively larger in proportion than the ascender and descender of a typeface (which it normally should be), then there is more legibility.

We should also take note that some typefaces are not meant to be read on-screen, meaning they would be less readable on-screen and they are more suitable for prints.

4. Leading and Line Length

The goal of setting text type is for

easy and prolonged reading. The field of type should full occupy a page.

Type size - Should be large enough to be read easily at arm's length (the distance between a book held on your lap and your eye)

Leading - The optimal amount of leading is usually a 2 to 2.5 points

size larger than the type size. Too tight of a leading would cause vertical

eye movement which causes readers to easily lose their focus on the text. Too

loose creates unnecessary blank stripes between the lines that distract the

readers from the text.

|

|

Figure 2.4 An example of leading. |

ALWAYS decide on the type size first, then the leading and lastly the line length.

5. Type Specimen Book

It is a book that shows samples of typefaces

in various types, type sizes, leading and line lengths. Designers test out

different combinations of type sizes, leading and line lengths, then compile

them into a sheet or book and ultimately decide on one that best suits the

material on hand. Depending on the final output of the material, one may view

it directly on the screen or have it printed.

It is useful to enlarge the type size by 400% on the screen to get a clear sense of the relationship between the ascender and the descender.

|

| Figure 2.5 An example of a type specimen sheet of the typeface 'Spartan Heavy'. |

Week 4

Text6. Indicating Paragraphs

Line space - The space between the descender of a sentence and the descender of another sentence.

Leading - The space between two sentences.

Ideally, paragraph space should be the same as the line space. For example, if the line space is 12 pt, then the paragraph space should be 12 pt as well. This is to ensure cross-alignment across columns of text.

|

| Figure 2.6 An example that shows the difference between line space and leading. |

Different ways to indicate paragraphs

- Pilcrow (¶) - A symbol used to indicate paragraphs, however, it is seldom used today.

-

Indentation - Usually the indent is the same size as the line spacing or the

point size of the text. Too much indentation would cause ragging which may

affect the readability. Indentation is best used when the text is

justified.

- Extended paragraphs - It creates unusually wide columns of text. Mostly used in academic writing.

Widow - A short line of type left alone at the end of a column of text.

Orphan - A short line of type left alone at the start of a new column.

AVOID the occurrence of widows and orphans.

|

| Figure 2.7 An example of a widow and an orphan. |

8. Highlighting Text

Ways of highlighting text

- Use italics.

- Make the text bold.

- Use a different typeface and make it bold (take note to reduce the point size of a sans serifs typeface by .5 to match the x-height of a serif typeface)

- Use a different colour.

- Place a field of colour at the back of the text.

- Place certain typographic elements outside the left margin of a column of type (e.g quotation marks, bullets, etc.)

|

| Figure 2.8 The symbols on top are primes, and the symbols at the bottom are quotation marks. |

9. Headline within Text

The subdivisions within the text of a chapter can be labelled as A, B and C heads according to the level of importance. We need to make sure the heads have a clear signification between the relationship of the texts.

A head - It creates a clear break between the topics within a section. These heads can be set in a different font, larger than the text, in small caps or in bold.

|

| Figure 2.9 Examples of A heads. |

|

| Figure 3. Examples of B heads. |

C head - It highlights specific facets of materials within the B head text.

|

| Figure 3.1 Examples of C heads. |

10. Cross Alignment

Cross aligning the headlines and captions within text type reinforces the structure of the page while producing complementary vertical rhythms.

Week 5

Letters1. Understanding Letterforms

Uppercase letters that are seemingly symmetrical are very often not symmetrical at all. For example, upon closer examination of the letter A in Baskerville form (Figure 1.), the brackets connecting the serifs and the stem are designed with different arcs. This underscores the meticulous attention given to details when type designers create a typeface.

|

| Figure 1. The brackets are designed with unique arcs. |

2. Maintaining X-heights

The curved strokes (i.e. the letter 's') of a letterform usually exceed the median and/or baseline slightly in order to appear to be the same size as other letterforms. Otherwise, the said letters would appear smaller in comparison with other letters.

3. Form / Counterform

4. Contrast

The basics of Graphic designs are applied directly to typography. Naturally, we can see the use of contrast in designing types.

|

| Figure 1.1 Various uses of contrast in typography. |

INSTRUCTIONS

Task 1: Exercise 1 - Type Expressions

Students should compose and express 4 words using the 10 typefaces given. Through iteration, students should use the appropriate typeface to compose the letters in a manner that allows the meaning of the letters to be visible.

There were six words given for this task - cough, pop, squeeze, explode, grow and decay. The word 'cough' was mandatory and we need to choose another three from the list. My choice of words is cough, grow, squeeze and explode.

Required software: Adobe Illustrator

|

| Figure 1. Pencil sketches for 'cough'. Week 2 (4/4/2022). |

|

| Figure 1.1 Pencil sketches for 'grow'. Week 2 (4/4/2022). |

|

| Figure 1.2 Sketches for 'grow' (#1A - #1F). Week 2 (4/4/2022). |

|

| Figure 1.3 Sketches for 'squeeze' (#2A - #2D) and 'cough' (#3A - #3B). Week 2 (4/4/2022). |

|

| Figure 1.4 Sketches for 'explode' (#4A - #4D) and 'decay' (#5A). Week 2 (4/4/2022). |

Based on Mr Vinod's feedback, I picked out one sketch for 'cough', 'explode', 'squeeze', and 'grow' for further development.

|

| Figure 1.5 Various designs for 'squeeze', 'explode', 'cough'. Week 2 (7/4/2022). |

|

| Figure 1.6 Final design for the words chosen. Week 2 (7/4/2022). |

I compiled the four designs into the template given and I would present it in the following lecture (Week 3) to receive feedback from Mr Vinod.

In Week 3, Mr Vinod provided his feedback on the four designs of type

expression. Based on his feedback and individual instructions in class,

I managed to create a ripple effect for the word 'cough' (Figure 1.7).

The effect can be created by creating several circles of different sizes

and aligning them at a centre point. Then, apply 'Outline Stroke' to the

group of circles and place the group on top of the letters o, u, g and

h. Next, select all elements, open Pathfinder and apply the Shape Mode

called 'Exclude'. Finally, delete the unwanted strokes of the circles

and we are done (Figure 1.7)!

|

| Figure 1.7 Outcome of the ripple effect. Week 3 (12/4/2022). |

The outcome did not quite resonate with me, so I played around with the effects and landed on 'Twist' (Figure 1.8). However, after reviewing the design with a fresh pair of eyes, the effect seemed too heavy and overshadowed the ripple. Therefore, I toned down the angle of the twist to 10%.

|

| Figure 1.8 Outcome of the combination of the ripple effect and the twist effect. Week 3 (12/4/2022). |

|

| Figure 1.9 Final design for type expression. Week 3 (12/4/2022). |

|

| Figure 2. Simple sketches of the frames. Week 3 (11/4/2022). |

|

| Figure 2.1 Creating and sequencing the frames for the animation. Week 3 (11/4/2022). |

For this particular word, I had to develop the frames reversely, meaning I would start with the final frame and work my way backwards to the initial frame. In the end, a total of 14 frames were created. Next, I load the frames into Photoshop and began sequencing the frames into the timeline. At first, I included all frames but it made the explosion appear too 'soft' and not loud enough. Hence, I reduced a couple of frames and the result seemed better.

|

| Figure 2.2 Attempt #1 for type expression animation. Week 3 (11/4/2022). |

|

|

Figure 2.3 Attempt #2 for type expression animation. Week 3

(11/4/2022). |

|

| Figure 2.4 Attempt #3 for type expression animation. Week 3 (12/4/2022). |

Final Submission for Exercise 1 - Type Expressions

|

| Figure 2.5 Final submission for Task 1 - Type Expressions (JPEG). Week 3 (12/4/2022). |

|

| Figure 2.7 Final submission for Task 1 - Type Expressions (GIF). Week 3 (12/4/2022). |

Task 1: Exercise 2 - Text Formatting

|

| Figure 2.8 Setting up the typefaces for the practice. Week 4 (20/4/2022). |

|

| Figure 2.9 Before and after kerning and spacing. Week 4 (22/4/2022). |

|

|

Figure 3. Changing the capital letters from semibold italics to

italics after realising the capitals seemed too heavy. Week 4

(22/4/2022). |

|

| Figure 3. A comparison between the regular lowercase and uppercase combination and all uppercase letters using Futura Std. Week 4 (22/4/2022). |

|

| Figure 3.1 Text formatting with kerning and spacing. Week 4 (22/4/2022). |

2/4 of Text Formatting: Font Size, Leading, Line Length and Paragraph Spacing

- A standard margin that is equal on all sides is less appealing, we should take note to manipulate the margins to make it more attractive.

- The ideal point size of the text within A4 and A3 is between 8 to 12

- Ideal line length: 55 - 65 characters (body text)

- Ideal leading: point size + 2/2.5/3 (e.g if the point size is 9, then the leading is either 11, 11.5 or 12 depending on the typeface).

- Paragraph spacing = leading

- Make sure the negative and positive field of the body text is even (middle grey value).

- Read through the material on hand to understand the hierarchy of information.

- Avoid formatting body text in different sizes - Maintain the same text width for the same piece of information, otherwise, the readers might think it is a separate piece of information.

- Apply kerning and spacing to reduce the ragging of one edge - do not exceed +3/-3 for tracking.

- Turn of hyphenation - if there is too much ragging, adjust the kerning and tracking when necessary.

- The suggested alignment is left align and left justify, avoid right align for a large amount of text.

- When using full justify, make sure to increase the column interval by about 2 - 5 mm to give more space between columns.

- Avoid widows and orphans.

- Pay attention to the visual hierarchy of the layout.

- Leading of heading = original leading x 2 (e.g if the original leading is 11 pt, then the new leading is 22 pt)

- Turn on Baseline Grid to help achieve cross alignment

- Adjust baseline grid to match the body text - Preference > Grids > match 'Increment Every' to current leading > adjust 'View Threshold' if necessary

|

||

Figure 3.2 Placing the provided text in InDesign. Week 5

(24/4/2022).

|

In one of my attempts of applying left-justified alignment, I came across some widows in the text. To eliminate the widows (Figure 3.4), I first apply a force line break to the second last line of the paragraph and apply a bit of tracking to the line to achieve smooth ragging. However, using a force line break led to the 'rivers' in the paragraph (the awkward blank space between the words in a line), so I undo the force line break and just used tracking instead (Figure 3.5).

|

| Figure 3.4 An issue of widows. Week 5 (24/4/2022). |

|

|

| Figure 3.5 Eliminating the widow using tracking. Week 5 (24/4/2022). |

|

|

Figure 3.6 An overview of the eight attempts for Exercise 2. Week

5 (25/4/2022).

|

|

| Figure 3.7 Attempt #1 for text formatting. Week 5 (25/4/2022). |

|

| Figure 3.8 Attempt #5 for text formatting. Week 5 (25/4/2022). |

|

| Figure 4. Attempt #8 for text formatting. Week 5 (24/4/2022). |

Final Submission for Exercise 2 - Text Formatting

|

| Figure 4.1 A screen capture of the final outcome for Text Formatting with the guides, baseline grid and hidden characters. Week 5 (26/4/2022). |

|

| Figure 4.2 Final submission for Task 1 - Text Formatting (JPEG). Week 5 (26/4/2022). |

Font: Adobe Caslon Pro

FEEDBACK

Week 1

General Feedback: N/ASpecific Feedback: N/A

Week 2

General Feedback: There are sufficient idea explorations. Mr Vinod advised that it is always better to start sketching with a pen and paper first as this practice allows more creative exploration. It is also beneficial for our cognitive development.- Grow (#1A - #1F)

- #1E - Simple and elegant solution. Mr Vinod suggested using the original 'w' and then creating the arrow. No need to distort the 'w'.

- #1F had the highest acknowledgement.

- Squeeze (#2A - #2D) - #2D had the most visual impact. Mr Vinod suggested using Univers LT Std condensed as the font. Avoid distorting the typeface as much as possible.

- Cough (#3A - #3B) - He suggested using the ripple effect to visualise the vibration of a cough. He instructed converting the type into a vector (Type --> Create Outlines) before adding the effect.

- Explode (#4A - #4D)

- #4A - Mr Vinod suggested using the Knife tool to cut up the ‘O’ for a scatter effect. Similarly, he suggested using the same effect on the other letters and making them lay down to express the aftermath of the explosion.

-

#4C - Interesting take. The design did give a sense of explosion

but the impact was not strong enough. Try scaling up to make the

effect look stronger and more violent.

Week 3

General Feedback: 'Cough' and 'explode' is good.Specific Feedback: Try to avoid designing at a 45 degree as it creates unnecessary tension due to its imbalance nature. 'Squeeze' is good but it would be better if you didn't distort the typeface. For the 'explode' gif, the action appeared too slow, try making it faster. Remember to leave a pause at the end of the loop.

Week 4

General Feedback: N/ASpecific Feedback: N/A

Week 5

General Feedback:- Make sure to fill in your feedback in the correct column in the spreadsheet.

- Make sure the final submitted image is 300 ppi.

- Make sure to complete the reflection and the further readings are up-to-date.

- The final submission should include one version that includes the guides, the baseline grids and hidden characters

- Included the necessary details below the document of your final submission (ie. font, typeface, font size, leading, paragraph spacing, average characters per line, alignment, margins, columns, gutter (for columns))

- The quality of the lecture section is not graded - just included whatever you learned from the lecture, the purpose is to capture your learning and help you refresh your memory.

-

When you format your blog, there should be a hierarchy of

visuals. There should be a clear distinction between the

heading, subtext and body text.

- Avoid ‘rivers’ in the text.

- Do not use full-justified alignment.

- Reduce the margin space on top.

- Move the heading upwards.

- Align the subtext with the top edge of the second column of body text.

- Reduce the widow.

- Move the caption upwards to align with the bottom edge of the body text.

-

Conduct some visual research and study the examples of layout.

- Use images that are directly related to Helvetica.

- It is not necessary to fill up the entire space of the page.

-

Avoid using condensed typefaces for a large amount of text.

REFLECTION

ExperienceI enjoyed attending physical classes for tutorials and practicals. It allowed me to receive real-time feedback from the facilitator and I could refine my work on the spot. I really enjoy the feedback section where we get to see other students' creativity, thought processes and approaches to the task. Using Facebook as the main communication platform is a fairly foreign approach for me. I was not used to using the app for educational purposes, and I am still in the midst of getting familiarised with the platform. For this task, I learned about the history, the terminologies and the basics of typography. During the initial stages of Exercise 1, I had difficulties generating ideas because the given words have very limited meanings and it was a constraint to my ideation. Since everyone was working on the same set of words, I knew for a fact that we would come across similar ideas and sketches. Therefore, I tried my best to produce some work that is unique. I would not say that my final outcomes are particularly outstanding but I gave myself some credit for doing sufficient exploration. Surprisingly, text formatting was a relatively easy task to complete. The task itself could be easy if one followed closely the instructions in the lecture videos. However, I still found it difficult to create smooth ragging and maintain grey value. I was very tempted to apply tracking more than three times just to achieve the smooth ragging. Another challenging aspect of the task for me was navigating the tools in InDesign and memorising the shortcut keys. I am more familiar with Illustrator and it can be confusing when both software utilises the same shortcut key but for different actions.

I found myself rushing through the task which led to not doing sufficient research on the topic and task before attempting it. I observed that my attention span in class has decreased and occasionally I would miss out on many important announcements regarding the task and the module in general.

One of the significant findings of completing this task is to always prioritise the readability and legibility of the text while maintaining a level of visual aesthetic in the design. I used to think that typography is about designing fancy and aesthetical fonts and typefaces, but now I realised that it is more about understanding the characteristics of different typefaces and how we utilise the characteristics to format text with good readability.

FURTHER READING

Week 1

|

| Figure 1. The book cover of 'Typography Essentials Revised and Updated: 100 Design Principles for Working with Type' by Ina Saltz, 2019. |

Each letter is a shape of its own. Other than its original function as an alphabetic unit, the shape of a letter can be used as an illustration, icon and graphic point. The letter itself is expressive, as a simple silhouette, an outline and a container of colour, texture and pattern. The space inside and around the letter, known as counter space or negative space, is an important design element and should be utilised more in designs. Every feature of a letter serves a role in conveying messages; manipulating and detailing certain features of a letter helps to communicate certain messages. However, designers should always keep in mind painting a balance between the visual and readability of the letterform.

Reference

Ina Saltz. (2019).

Typography Essentials Revised and Updated : 100 Design Principles

for Working with Type: Vol. Revised and updated.

Rockport Publishers.

Week 2

|

| Figure 1.1 The book cover of 'Typographic Design: Form and Communication' by Rob Carter, Ben Day and Philip B. Meggs (2012). |

Book of the Week: Typographic Design: Form and Communication by Rob Carter, Ben Day and Philip B. Meggs

Chapter: Typographic Syntax

Typographic syntax refers to the

process of arranging elements into a cohesive whole, the elements include

the letters, words, lines, columns and margins.

- The letter - Other than functioning as a unit that is part of a word, it can also be used individually or combined with other letters to work as a sign. It utilises the dynamic and interaction with the surrounding negative space to create type expressions.

- The word - Consider the relationship between the form and the counterform of the word. Utilise the negative and positive space around the words and the letters to create harmony.

- The columns and margins - The harmonious space of a layout is also governed by the proportion of the column height to weight, texture (the tactile appearance of the type) and tone (the lightness and weight of the type).

Week 3

|

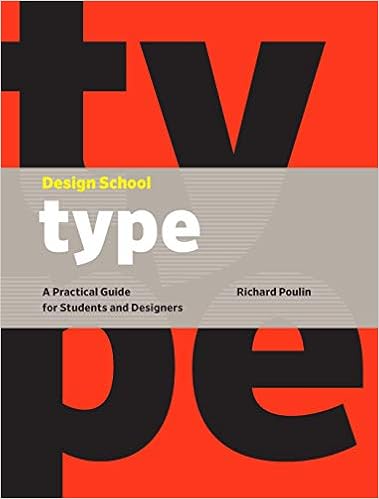

| Figure 1.2 The book cover of 'Design School: Type: A Practical Guide for Students and Designers' by Richard Poulin (2017) |

Book of the Week: Design School: Type: A Practical Guide for Students and Designers by Richard Poulin.

During the selection of typefaces, one should utilise the historical and technical knowledge of type, as well as the knowledge of functional and aesthetical qualities of letterforms and typographic compositions.

Week 4

|

| Figure 1.2 The book cover of 'Design School: Type: A Practical Guide for Students and Designers' by Richard Poulin (2017) |

Readability refers to the measure of how difficult or easy it is for a reader to understand a piece of written text. Legibility is defined as the measure of how difficult or easy it is for a reader to distinguish the individual letters from each other, and the words they form. Readability is affected by the manipulation of line length, character count per line, spacing and case. The majority of typefaces with good legibility share features such as having a larger x-height and counters, as well as unique and distinct letterform profiles.

Comments

Post a Comment